In the field of metallurgy, a shape-memory alloy (SMA) is an alloy that, when heated, regains its previously distorted (or “remembered”) shape. Other names for it include smart metal, memory metal, etc. By fixing the required shape and applying a thermal treatment, the “memorized geometry” can be altered. For instance, a wire can be trained to learn the shape of a coil spring. The product offers a solid-state, incredibly lightweight substitute for traditional actuators.

The two phases, i.e., martensite and austenite, occur in SMAs. At lower temperatures, the relatively soft and readily deformed phase of SMAs is called martensite. Higher temperatures cause austenite, which is the stronger phase of SMAs, to form. SMAs can be made by many metallic elements like alloying zinc, copper, gold, and iron, but one of the most used plus important alloys is nickel-titanium (NiTi) alloys. When cooled, NiTi alloys transform from austenite to martensite and are typically more costly.

For the majority of usages, NiTi-based SMAs are far more desirable. The SMA changes its shape elastically with reversible strain when a force from outside falls below the martensite yield strength, which is roughly 8.4% strain for NiTi alloys and 5-6 % strain for copper-based alloys. Beyond this limit, nevertheless, a significant non-elastic deformation (permanent plastic deformation) will occur. The majority of applications will limit the strain level, for example, for NiTi alloys to 4% or less.

Thermodynamically, austenite (B2 cubic) is preferred at larger temperatures, but martensite is preferred at lower temperatures. Cooling austenite into martensite adds internal strain energy to the martensitic phase because the lattice sizes and symmetry of these structures differ. The martensitic phase creates several twins to lower this energy; this is known as “self-accommodating twinning.”

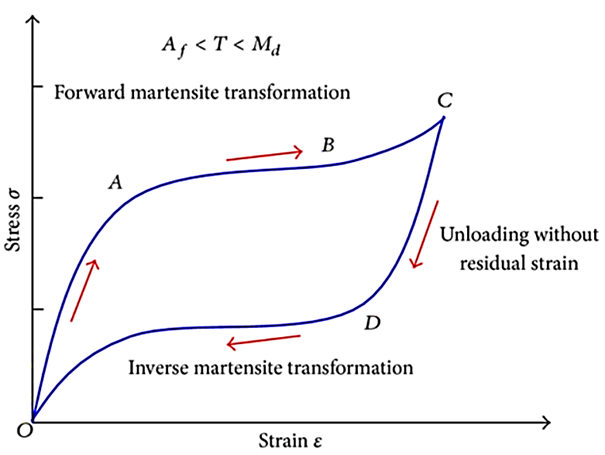

The picture shows that Austenite turns into martensite when the stress is greater than the martensitic stress, resulting in significant stresses until the transformation is finished. Below the austenitic stress, martensite reverts to austenite upon unloading, recovering almost all of the strain, frequently more than 10% in certain SMAs. The work completed each cycle is represented by a hysteresis loop created by this reversible phase change, which is essential for many applications.

Orthopaedics, neuroscience, cardiac surgery, and diagnostic radiology are just a few of the healthcare fields that use SMAs. Other medical applications include dental care, stents, sutures, anchors for providing tendon to bone, and spectacle frames. While stainless steel stents tend to drive blood arteries straight, SMA stents are significantly more tolerant of vessel bends and lumen shapes.

https://sci-hub.se/https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0261306913011345

![]()